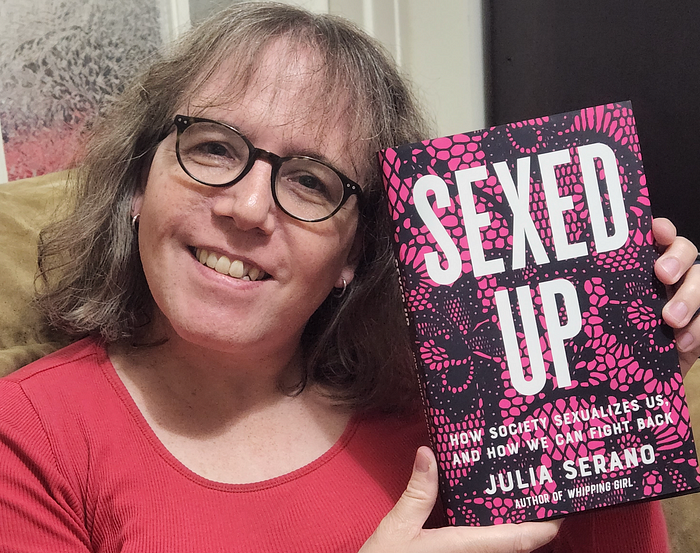

Sexed Up: a chapter-by-chapter preview of my new book

My latest book, Sexed Up: How Society Sexualizes Us, and How We Can Fight Back, is primarily about sexualization — when we nonconsensually reduce a person to their real or imagined sexual attributes (their body, behaviors, or desires) rather than view them as a whole person. We tend to project certain sexual motives and meanings onto some subgroups of people but not others. In Sexed Up, I examine why this is.

Feminists have long critiqued the ways in which women are sexualized in our straight-male-centric culture (via objectification, slut-shaming, sexual harassment, and sexual violence). While I have experienced all these manifestations of sexualization when people presume I am a cisgender woman, if they are aware that I’m transgender, they often sexualize me in a host of other ways, viewing me as sexually deviant, or predatory, or hypersexual, or desperate, or undesirable, or exotic, or as a “fetish object.” Notably, some of these additional forms of sexualization are projected onto other minority groups, including other LGBTQIA+ folks, people of color, people with disabilities, poor and working-class people, and so on.

While many past writers and theorists have considered these different forms of sexualization separately, they all felt deeply interconnected to me, so I set out to understand how they arise, and why being reduced to the status of a “sexual being” tends to have a delegitimizing or degrading effect on people. In Sexed Up, you’ll find my answers to these questions, plus my suggestions for how we can work to challenge all forms of sexualization moving forward.

Whenever I stumble upon a nonfiction book that piques my interest, I will often page through the Introduction looking for a chapter-by-chapter preview that maps out all the ground the book covers, and details which chapters address which specific issues. While Sexed Up’s Introduction provides an overview of the book, it does not include a chapter-by-chapter preview. So I thought that I would offer one here.

I begin the book by describing four different unconscious mindsets that shape how we perceive and interpret sex and sexuality, and which all contribute to sexualization to some degree.

Chapter 1 is called “The Two Filing Cabinets in Our Minds.” It draws from research into how we learn to categorize people according to sex, and shares anecdotes from my own transition demonstrating how, once we presume that someone is female or male, we filter away all sorts of other information about them. In other words, we don’t see people per se; we see women and men, and that unconscious determination shapes all of our subsequent interpretations of them.

Chapter 2 is called “Opposites.” It includes examples of some of the very different expectations, value judgments, and meanings that people projected onto me as a woman versus what I previously experienced when perceived as a man. I go onto show how many of these meanings — such as the assumptions that men are strong and tough, while women are weak and fragile; that men are active and assertive, while women are passive and receptive; that men are serious and functional, while women are frivolous and ornamental; and that men are sincere and rational, while women are manipulative and emotional — all stem directly from our tendency to view the sexes as “opposites” rather than as simply different or overlapping. Analogous Opposites mindsets also influence how we view other marginalized groups relative to the dominant/majority.

Chapter 3 is “Unwanted Attention.” It begins with my account of the street remarks and harassment that I received once people began perceiving me as female. Rather than frame these experiences in terms of sexual objectification (as feminists historically have), I instead explain them in terms of the Unmarked/Marked mindset: where some groups (e.g., women) are “marked” relative to some taken-for-granted default group (in this case, men), and thus receive undue attention as a result. Essentially, marked groups are perceived as “public spectacles” that seem to give off “phantom invitations,” which is why marked groups are often falsely accused of “asking for” any unwanted attention that they receive. I go onto show how this mindset more generally explains the increased scrutiny and questioning that minorities face, which can be further compounded for individuals who are marginalized in multiple ways.

Chapter 4 is “The Predator/Prey Mindset” — this is the framework through which most of us were socialized to understand sex and sexuality. In it, men are viewed as sexual initiators or aggressors (i.e., Predators), whereas women are viewed as “sexual objects” that men pursue (i.e., Prey). This mindset is built into our culture’s standard sexual script, in which the man is expected to make the first move (and all successive moves) — that is, he acts, whereas the woman merely reacts, either by accepting or acquiescing to his overtures, or else fending him off. I go on to show how this mindset enables the sexualization of women in numerous ways. Relevant chapter subheadings include: “The Virgin/Whore Double Bind and Sexualization”; “Phantom Invitations and ‘Leading Men On’”; “‘Boys Will Be Boys’ and ‘She Should Have Known Better’”; “‘Clothes Don’t Make the Man,’ but ‘She Was Asking for It’”; and “Women Are Sex, and Sex Is Bad.” (To be clear, these all refer to popular sentiments that I critique, rather than how things actually are.)

While Chapter 4 focuses primarily on women’s predicaments, Chapter 5 (called “Confused Sluts”) looks at how the Predator/Prey mindset negatively impacts men. For instance, it leads many men to develop a mystified view of women, one that obscures many of the obstacles that women face (especially with regards to sexualization), while simultaneously putting pressure on men to distance themselves from any behaviors or interests that are culturally coded as feminine. Furthermore, the notion that men are “predators” and not “prey” makes it difficult for many people to contemplate or take seriously the fact that one in four men experience sexual violence in their lives, and it can also lead some subgroups of men — particularly men of color — to be stereotyped en masse as “sexual predators.”

In Chapter 6 (“Sexualization, Objectification, and Stigma”), I compare and contrast two models for thinking about sexualization. The most commonly accepted model within feminism has been largely centered on objectification, and specifically, the argument that it dehumanizes women, thereby allowing men to exploit or use us for their own sexual satisfaction. While this certainly accounts for some instances of sexualization, it overlooks many others. So I instead propose a non-mutually-exclusive stigma model of sexualization. Basically, some people in our culture (such as women) are “marked by sex” in the eyes of others, and this often results in their stigmatization. As a result, marked individuals may feel compelled to hide or play down their “sex,” and may be shamed or disparaged if it “shows” or “surfaces” in any way, whereas those who remain unmarked are largely immune from this sexual stigma. In addition to accounting for many women’s experiences, this stigma model is more readily applied to the sexualization of other marginalized groups.

Chapter 7 is “Intersectionality and Hypersexualization.” In it, I explain how intersectional marginalization arises, at least in part, from the previously described mindsets, and how it can lead people to misperceive or mischaracterize marginalized groups as “excessively sexual” (and thus, “marked by sex”). Often this results in marginalized men being stereotyped as sexually predatory, and marginalized women stereotyped as sexually promiscuous or available, although it can manifest in other ways as well. I also chronicle the various ways in which Black, Latinx, Native American, Asian, poor, and disabled people have been hypersexualized throughout recent history. Often, this hypersexualization goes hand in hand with political propaganda stoking fears that the marginalized group’s “excessively sexual” nature will have a “contaminating” or “corrupting” influence on the supposedly “pure” dominant/majority group.

Chapter 8 is called “Queer as a Three Dollar Bill,” and it’s about the different ways in which LGBTQIA+ people are sexualized for our failure or refusal to adhere to Predator/Prey’s roles and rules. Many of the sexualizing stereotypes we face are premised on the notion that we are “fakes” or “deceivers” who sexually “prey” on innocent straight people. And because sexual stigma is often viewed as “contaminating” and “contagious,” the straight majority has long imagined that our mere presence might “compromise” their own genders and sexualities, potentially “turning them queer” in the process. Today in 2022, we are living through an intense anti-transgender moral panic that baselessly accuses us (and our supporters) of supposedly being “groomers” and “sexual threats” to women and children. In Sexed Up, I discuss virtually identical campaigns waged against gay, Black, and Jewish people in the past, and make the case that we must confront sexualization head-on if we wish to bring an end to anti-LGBTQIA+ prejudice and these recurring moral panics.

Chapter 9, “You Make Me Sick,” explores the Fetish mindset, which occurs when a marginalized group is socially deemed “undesirable” for some reason or another. As a direct consequence, people who find such individuals attractive are often presumed to have some kind of “fetish” — that is, a pathological sexual desire. This mindset essentially sexualizes both parties: The person who experiences said attraction becomes a “fetishist,” while the marginalized individual is reduced to a “fetish object.” This can play out in all sorts of complex ways, often depending upon how stigmatized the group in question is. In addition to unpacking this mindset, I show how it is driven by sexual stigma, reveal the connections between stigma and disgust (and how to unlearn them both), and examine the “exoticization of the Other.”

Chapter 10 is called “Fantasies and Hierarchies.” It begins with my critique of the concepts of “perversion” and “paraphilias,” which are socially derived categories (based upon what’s culturally deemed “normal”) rather than having any actual scientific basis. I then forward my own Sexual Elements/Meanings Framework, which better describes the vast diversity in sexual “turn-ons” and “turn-offs” — akin to how we all develop different tastes when it comes to food. I go on to consider how social hierarchies (such as Predator/Prey) may influence our desires, albeit not always in a straightforward or predictable fashion. While some feminists have condemned forms of sex and sexuality that appear to be influenced by social hierarchies, I detail numerous flaws to this approach, and argue that we should instead strive to be ethically sexual. This includes (but is not limited to) rejecting nonconsensuality; refraining from divvying up sex into “good” and “bad” categories; self-examining desire; and severing sex from stigma.

The final chapter is “Rethinking Sex and Challenging Sexualization.” In it, I make the case that we need to challenge all forms of sexualization simultaneously, and I provide several strategies to do so. One such strategy is “Going Off-Script,” by which I mean abandoning the Predator/Prey script and seeking out more collaborative ways to be romantic and sexual. In the section “Bad Actors and Me Too,” I discuss ways to mitigate (if not outright eliminate) sexual violence. And in the section “Sexual Dystopias and Utopias,” I explain why the “hiding sex” strategy to end sexualization will inevitably backfire. To sum up this chapter, as well as the book as a whole: We should strive to foster sexual equity without sacrificing sexual diversity in the process.

So that’s a quick rundown of Sexed Up. If you want to read praise for, reviews of, and excerpts from the book, you can find those on my Sexed Up webpage. At the moment, it’s available in hardcover, ebook, and audiobook — those links will take you to the Seal Press website, which offers a variety of book sellers to choose from. You can also go to your local bookstore and/or library and ask them to order a copy for you.